Since the earliest settlements on the Korean Peninsula and in southeastern Manchuria during prehistoric times, the people of Korea have developed a distinctive culture based on their unique artistic sensibility. The geographical conditions of the peninsula provided Koreans with opportunities to receive both continental and maritime cultures and ample resources, which in turn enabled them to form unique cultures of interest to and value for the rest of humanity, both then and now.

Gyeongju Historic Areas. Gyeongju was the capital of Silla for about one millennium. The city still contains a wealth of archaeological remains from the Kingdom, and hence is often dubbed as “a museum without walls or roof.” The photo shows a scene of the Silla mound tombs located in the city.

Korea’s vibrant cultural legacy, comprising music, art, literature, dance, architecture, clothing and cuisine, offers a delightful combination of tradition and modernity, and is now appreciated in many parts of the world.

At the present time, Korean arts and culture are attracting many enthusiasts around the world. Korea’s cultural and artistic achievements through the ages are now leading many of its young talents to the world’s most prestigious music and dance competitions, while its literary works are being translated into many different languages for global readers. More recently, Korean pop artists have attracted huge numbers of admirers across the world, the most spectacular success being Psy’s global hit Gangnam Style.

The cultural prosperity Korea has enjoyed lately would have not been possible without its traditional culture and arts, which were built on the Korean people’s traits of tenacity and perseverance combined with an artistic sensibility that has matured throughout the country’s long history. The unique artistic sensibility reflected in the diverse artifacts and tomb murals of the Three Kingdoms Period became richer and more profound as Korea progressed through the periods of Unified Silla (676-935), Goryeo (918-1392) and Joseon (1392-1910). This aesthetic sensibility has been handed down through the generations to the Korean artists, and even ordinary members of the public, of our time.

Korea preserves a wealth of priceless cultural heritage, some of which have been inscribed on the lists of human legacies protected by UNESCO. Currently, a total of thirty-eight Korean heritage items are listed either as World Heritage Sites or Masterpieces of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity, or have been included on UNESCO’s Memory of the World Register.

UNESCO Heritage in Korea

World Heritage Sites

Changdeokgung Palace

Changdeokgung Palace, located in Waryong-dong, Jongno-gu, Seoul, is one of the five Royal Palaces of Joseon (1392-1910), and still contains the original palace structures and other remains intact. It was built in 1405 as a Royal Villa but became the Joseon Dynasty’s official Royal Residence after Gyeongbokgung, the original principal palace, was destroyed by fire in 1592 when Japanese forces invaded Korea. Thereafter it maintained its prestigious position until 1867, when Gyeongbokgung was and renovated and restored to its original status. Changdeokgung was listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1997.

Injeongjeon Hall in Changdeokgung Palace. The Palace Hall was used for important state events such as the Coronation of Kings, royal audiences, and formal reception of foreign envoys.

Although it was built during the Joseon Period. Changdeokgung shows traces of the influence of the architectural tradition of Goryeo, such as its location at the foot of a mountain. Royal palaces were typically built according to a layout planned to highlight the dignity and authority of its occupant, but the layout of Changdeokgung was planned to make the most of the characteristic geographical features of the skirt of Bugaksan Mountain. The original palace buildings have been preserved intact, including Donhwamun Gate, its main entrance, Injeongjeon Hall; Seonjeongjeon Hall, and a beautiful traditional garden to the rear of the main buildings. The palace also contains Nakseonjae, a compound of exquisite traditional buildings set up in the mid-19th century as a residence for members of the royal family.

Jongmyo Shrine

Jongmyo, located in Hunjeong-dong, Jongno-gu in Seoul, is the royal ancestral shrine of the Joseon Dynasty (1392-1910). It was built to house eighty-three spirit tablets of the Joseon Kings, their Queen Consorts, and direct ancestors of the dynasty’s founder who were posthumously invested with royal titles. As Joseon was founded according to Confucian ideology, its rulers considered it very important to put Confucian teachings into practice and sanctify the institutions where ancestral memorial tablets were enshrined.

Jongmyo Shrine. The central Confucian shrine of Joseon housing the spirit tablets of Joseon Kings and their Consorts.

The two main buildings at the Royal Shrine, Jeongjeon Hall and Yeongnyeongjeon Hall exhibit a fine symmetry, and there are differences in the height of the raised platform, the height to the eaves and the roof top, and the thickness of the columns according to their status. The entire sanctuary retains its original features, including the two shrine halls which exhibit the unique architectural style of the 16th century. Seasonal memorial rites commemorating the life and achievements of the royal ancestors of Joseon are still performed at the shrine.

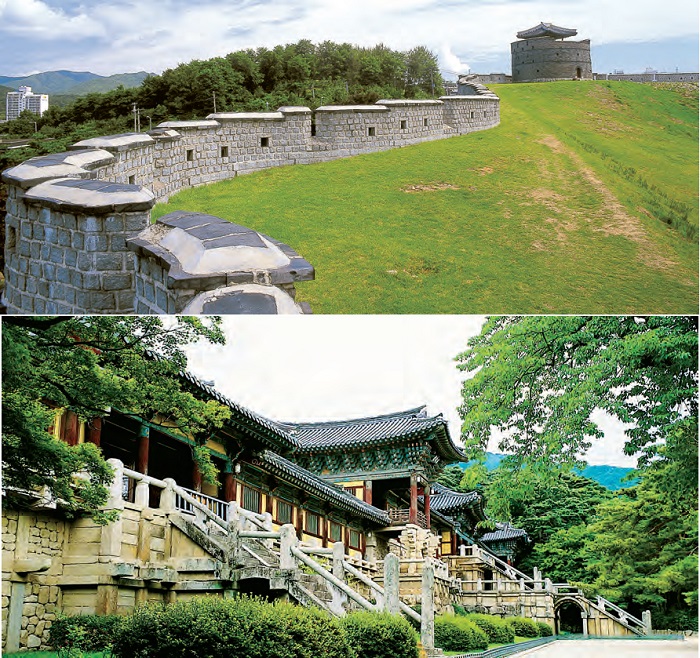

Hwaseong Fortress in Suwon

Located in today’s Jangan-gu of Suwon-si, Gyeonggi-do, Hwaseong is a large fortress (its walls extend for 5.7km) built in 1796 during the reign of King Jeongjo (r. 1776-1800) of the Joseon Dynasty. Construction of the fortress was begun after the King moved the grave of his father, Crown Prince Sado, from Yangju in Gyeonggi-do to its current location near the fortress. The fortification is elaborately and carefully designed to effectively perform its function of protecting the city enclosed within it. The construction of the fortress and related facilities involved the use of scientific devices developed by the distinguished Confucian thinker and writer Jeong Yak-yong (1762- 1836), including the Geojunggi (type of crane) and Nongno (pulley wheel) used to lift heavy building materials such as stones.

Seokguram Grotto and Bulguksa Temple

Seokguram, located on the middle slopes of Tohamsan Mountain in Gyeongju, Gyeongsangbuk-do, is a Buddhist hermitage with an artificial stone cave built in 774 to serve as a dharma hall. The hall houses an image of seated Buddha surrounded by his guardians and followers carved in relief, which is widely admired as a great masterpiece. The cave faces east and is designed so that the principal Buddha receives the first rays of the sun rising from the East Sea on his head.

Completed the same year as Seokguram Grotto, Bulguksa Temple consists of exquisite prayer halls and various monuments, including two stone pagodas, Dabotap and Seokgatap, standing in the front courtyard of the temple’s main prayer hall, Daeungjeon. The two pagodas are widely regarded as the finest extant Silla pagodas: the first is admired for its elaborately carved details, the second for its delightfully simple structure.

1. Hwaseong Fortress in Suwon This 18th century fortification was built on the basis of the most advanced knowledge and techniques known to both East and West at that time. 2. Bulguksa Temple This Silla temple established in the 6th century is architecturally known for being one of the finest examples of Buddhist doctrine anywhere in the world. 3, 4. Seokguram GrottoThe principal Buddha seated on a lofty lotus pedestal at the center of the grotto.

Dabotap, or the Pagoda of Abundant Treasures, is marked by a unique structure built with elaborately carved granite blocks. It also features on the face of the Korean 10 won coin. By contrast, Seokgatap, or the Pagoda of Shakyamuni, is better known for its delightfully simple structure which exhibits fine symmetry and balance. The pagoda is now generally regarded as the archetype of all the three-story stone pagodas built across Korea thereafter.

Among the other treasures preserved at the temple are the two exquisite stone bridges, Cheongungyo (Blue Cloud Bridge) and Baegungyo (White Cloud Bridge), leading to Daeungjeon, the temple’s principal dharma hall. The bridges symbolize the journey every Buddhist needs to make to reach the Pure Land of Bliss.

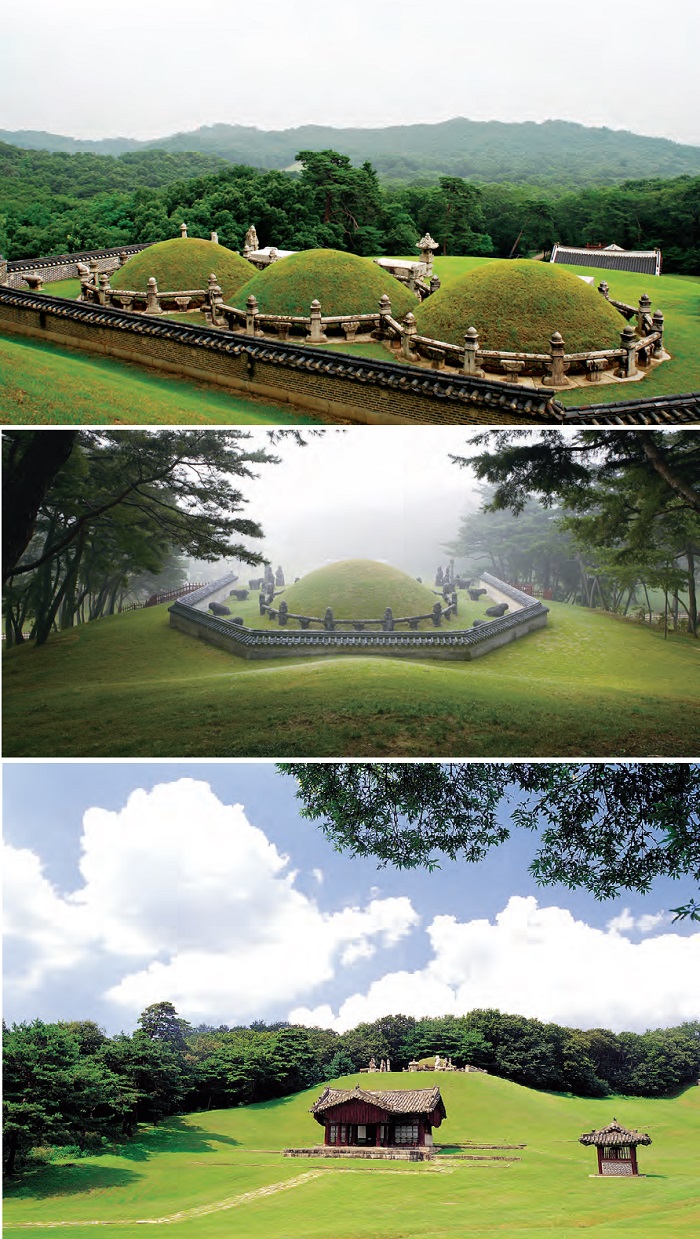

Royal Tombs of the Joseon Dynasty

The Joseon Dynasty (1392-1910) left behind a total of fortyfour tombs of its Kings and their Queen Consorts, most of which are located in and around the capital area including the cities of Guri, Goyang and Namyangju in Gyeonggi-do. Some of these Royal Tombs are arranged in small groups in the Donggureung, Seooreung, Seosamneung and Hongyureung. Of these, forty tombs are registered as UNESCO World Heritage Sites.

1. Donggureung A complex of Royal Tombs built for nine Joseon Kings and their seventeen Queens and Concubines. 2. Yeongneung The tomb of King Sejong and his consort Queen Soheon. 3. Mongneung The tomb of King Seonjo and his consort Queen Inmok.

The Royal Tombs of Joseon are highly regarded as tangible heritage that reflect the values held by the Korean people, which were drawn from Confucian ideology and the feng shui tradition. These historical remains are also valued highly for having been preserved in their original condition for anywhere from one to six hundred years.

Janggyeongpanjeon Depositories of Haeinsa Temple, Hapcheon

The Printing Woodblocks of the Tripitaka Koreana, which was made during the Goryeo Period (918-1392), are housed in two depositories specially made for that purpose in 1488 at Haeinsa Temple. As the oldest remaining buildings at the temple, the Tripitaka depositories are marked by the uniquely scientific and highly effective method of controlling ventilation and moisture to ensure the safe storage of the age-old woodblocks. The buildings were built side by side at the highest point (about 700m above sea level) in the precincts of Haeinsa Temple, which is located on the mid-slope of Gayasan Mountain.

What makes these depositories so special is their unique design which provides effective natural ventilation by exploiting the wind blowing in from the valley of Gayasan. Open lattice windows of different sizes are arranged in upper and lower rows on both the front and rear walls of the depositories to promote the optimum flow of air from the valley. Similarly, the floor, which was built by ramming layers of charcoal, clay, sand, salt and lime powder, also helps to control the humidity of the rooms.

Stone Warrior, Guardian of the Royal Tombs

Each of the royal tombs of Joseon consists of one or more semispherical mounds protected with curb stones set around the base, and with elaborately carved stone railings and stone animals, including a lamb and a tiger in particular, representing meekness and ferocity. In the front area there is a rectangular stone table that was used for offering sacrifices to the spirits of the royalty buried there, a tall octagonal stone pillar, a stone lantern, one or more pairs of stone guardians, and civil and military officials, with their horses. The mound is further protected by a low wall standing at the back and on both sides.

Namhansanseong Fortress

Namhansanseong Fortress, located about 25km southeast of Seoul, underwent large-scale restructuring in 1626, during the reign of King Injo of the Joseon Dynasty, to create a refuge for the King and his people in the event of a national emergency. The foundations of Jujangseong Fortress, built almost one thousand years earlier in 672, during the reign of King Munmu of Unified Silla, served as the base of the renovated structure.

Namhansanseong Fortress. A mountain fortress that served as a temporary capital during the Joseon Dynasty, showing how the techniques for building a fortress developed during the 7th-19th centuries.

The defensive position of the fortress was reinforced by exploiting the rugged topography of the mountain (average height: at least 480m). The perimeter of its wall is about 12.3km. According to a record dating from the Joseon Period, about 4,000 people lived in the town built inside the fortress.

Temporary palaces, Jongmyo Shrine, and Sajikdan Altar were built in the fortress in 1711 during the reign of King Sukjong of Joseon. The fortress is also a result of the wide-ranging exchanges made and wars waged between Korea (Joseon), Japan (Azuchi- Momoyama Period), and China (Ming and Qing) during the 16th-18th centuries. The introduction of cannons from western countries brought many changes to the weaponry inside the fortress and the way the fortress was built. The fortress is a “living record” of the changes in the way fortresses were built during the 7th-19th centuries.

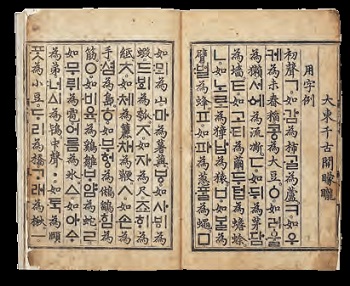

Hunminjeongeum Manuscript. The pages shown here contain a commentary on the three sounds, first, middle and last, that form the sound of a Korean character.

Hunminjeongeum (The Proper Sounds for the Instruction of the People)

Hangeul is the name of the Korean writing system and alphabet, which consists of letters inspired by the shapes formed by the human vocal organs during speech, making it very easy to learn and use. Hangeul was promulgated in 1446 by King Sejong, who helped devise it and named it Hunminjeongeum, or The Proper Sounds for the Instruction of the People. It was also in that same year that he ordered his scholars to publish The Hunminjeongeum haeryebon (Explanatory Edition) to provide detailed explanations of the purpose and guiding principles of the new writing system. One of these manuscripts is currently in the collection of the Kansong Art Museum and was included in UNESCO’s Memory of the World Register in 1997.

The invention of the Hunminjeongeum opened up a broad new horizon for all the Korean people, even women and those in the lowest social class, enabling them to learn to read and write and express themselves fully. The Hunminjeongeum alphabet originally consisted of 28 letters, but only 24 are used now. In 1989, UNESCO joined the Korean government to create the UNESCO King Sejong Literacy Prize, which it awards to organizations or individuals who display great merit and achieve particularly effective results in contributing to the promotion of literacy.

Joseon Wangjo Sillok: Annals of the Joseon Dynasty

The Joseon Dynasty left behind a vast collection of annual records of Joseon rulers and their officials covering the 472 years from 1392 to 1863. The records, Joseon wangjo sillok (Annals of the Joseon Dynasty), comprise 2,077 volumes and are stored at the Kyujanggak Institute for Korean Studies, Seoul National University.

The annals of each Joseon ruler were usually compiled after his death during the early phase of his successor’s rule based on the daily accounts, called “historical drafts” (sacho), made by historiographers. The annals are regarded as extremely valuable historical resources as they contain detailed information about the politics, economy, culture and other aspects of Joseon society.

Once the annals had been compiled and placed in the “history depositories” (sago), they would not be opened to anyone except in special circumstances where it was necessary to refer to past examples with regard to the formal conduct of important state ceremonies such as the memorial rites for royal ancestors or the reception of foreign envoys. Originally there were four history depositories, one in the Chunchugwan (Office of State Records) at the Royal Court, and three more in the main regional administrative hubs in the south, namely, Chungju, Jeonju and Seongju. However, these were destroyed in 1592 when Japan invaded Korea, and the Joseon Dynasty was compelled to build new depositories on some of the remotest mountains in the country, Myohyangsan, Taebaeksan, Odaesan and Manisan.

Ilseongnok Private journals concerning personal daily activities and state affairs kept by the rulers of late Joseon from 1760 to 1910.

This collection of documents contains the records of the Joseon rulers’ public life and their interactions with the bureaucracy; they were made on a daily basis by the Seungjeongwon, or Royal Secretariat, from the third month of 1623 to the eighth month of 1910. The records are collected in 3,243 volumes and include the details of royal edicts, reports and appeals from ministries and other government agencies. The diaries are currently kept in the Kyujanggak Institute for Korean Studies, Seoul National University.

Ilseongnok: Daily Records of the Royal Court and Important Officials

This vast collection of daily records made by the Kings of the late Joseon Period (from 1760 to 1910) is compiled in a total of 2,329 volumes. The records provide vivid and detailed information on the political situation in and around Korea and the ongoing cultural exchanges between east and west from the 18th to the 20th century.

Protocol on the Marriage of King Yeongjo and Queen Jeongsun (Joseon, 18th century). This is a manual of the state ceremony held for the marriage between King Yeongjo, the 21st ruler of Joseon, and Queen Jeongsun in 1759.

This collection of beautifully illustrated books contains official manuals recording the details of Court Ceremonies or events of national importance for the purpose of future reference. The most frequently treated subjects in these books are Royal Weddings, the investiture of Queens and Crown Princes, State and Royal Funerals, and the construction of Royal Tombs, although other state or royal occasions such as the “Royal Ploughing”, construction or renovation of Palace buildings, are included. As for the latter, those published to mark the construction of Hwaseong Fortress and King Jeongjo’s formal visit to the new walled city in the late 18th century are particularly famous. These publ ications were also stored in the history depositories, sadly resulting in the destruction of early Joseon works by fire during the Japanese Invasion of Korea in 1592. The remaining 3,895 volumes of Uigwe were published after the war, some of which were stolen by the French Army in 1866 and kept in the Bibliotheque nationale de France until 2011, when they were returned to Korea following an agreement between the governments of Korea and France.

Tripitaka Koreana Woodblocks A total of over 80,000 woodblocks carved with the entire canon of Buddhist scriptures available to Goryeo in the 13th century.

The collection of Tripitaka woodblocks stored at Haeinsa Temple (established 802) in Hapcheon-gun, Gyeongsangnamdo was made during the Goryeo Period (918-1392) under a national project that started in 1236 and took fifteen years to complete. The collection is generally known by the name Palman Daejanggyeong, literally “the Tripitaka of eighty thousand woodblocks,” as it consists of 81, 258 blocks of wood.

The Tripitaka Koreana woodblocks were made by the people of Goryeo who sought the Buddha’s magical power to repel the Mongol forces that had invaded and devastated their country in the 13th century. TheTripitaka Koreana is often compared with other Tripitaka editions produced by the Song, Yuan and Ming Dynasties in China, and has been highly praised for its richer and more complete content. The process of manufacturing the woodblocks played an important role in the development of printing and publication techniques in Korea.

Human Rights Documentary

Heritage 1980: Archives of the May 18th

Democratic Uprising in Gwangju

The May 18th Gwangju Uprising was a popular rebellion that took place in the city of Gwangju from May 18 to 27 1980, during which Gwangju’s citizens made a strong plea for democracy in Korea and actively opposed the then military dictatorship. The pro-democracy struggle in Gwangju ended tragically but exerted a powerful influence on similar democratic movements that spread across East Asia in the 1980s. This UNESCO inscription consists of the documents, videos, photographs and other forms of records made about the activities of Gwangju’s citizens during the movement, and the subsequent process of compensation for the victims, as collected by The May 18 Memorial Foundation, the National Archives and Records Service, the National Assembly Library, and various organizations in the USA.

Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity

Jongmyo Jeryeak (Royal Ancestral Rite and Ritual Music at Jongmyo Shrine) The Royal Ancestral Memorial Rite held seasonally at the Jongmyo Shrine involves the performance of the civil and military dances Munmu and Mumu.

Royal Ancestral Rite and Ritual Music

The Royal Ancestral Rite (Jongmyo Jerye) now held on the first Sunday of May to honor the deceased Joseon Kings and their Queen Consorts at the Jongmyo Shrine in Seoul remained one of the most important state ceremonies after the establishment of Joseon as a Confucian state in 1392. Designed to maintain the social order and promote solidarity, the ritual consists of performances of ceremonial orchestral music and dances praising the civil and military achievements of the Royal ancestors of Joseon. This age-old Confucian ritual combining splendid performances of music and dance is widely admired not only for the preservation of original features formed over 500 years ago, but also for its unique syncretic or composite art form.

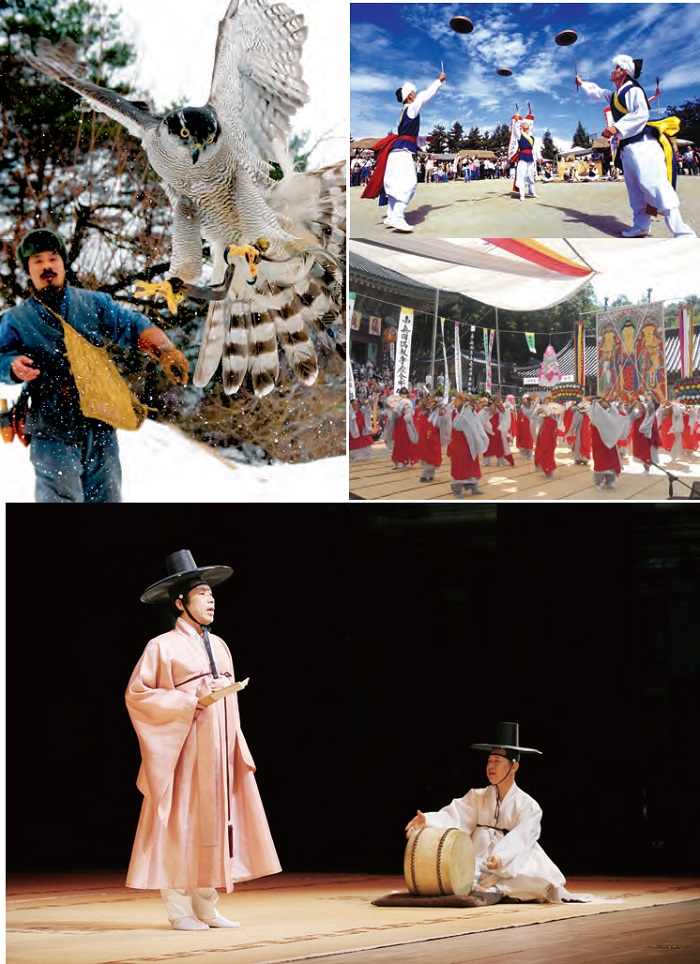

Pansori

Pansori is a genre of musical storytelling performed by a vocalist and a single drummer in which he or she combines singing (sori) with gestures (ballim) and narrative (aniri) to present an epic drama conceived from popular folk tales and well known historic events. The art form was established during the 18th century and has generated enthusiastic performers and audiences ever since.

Gangneung Danoje Festival

This summer festival held in and around Gangneung, Gangwondo, for about 30 days from the fifth day of the fifth lunar month to Dano Day on the fifth day of the fifth lunar month, is one of Korea’s oldest folk festivals and has been preserved more or less in its original form since its emergence many centuries ago. The festival starts with the traditional ritual of honoring the mountain god of Daegwallyeong and continues with a great variety of folk games, events and rituals during which prayers are offered for a good harvest, the peace and prosperity of villages and individual homes, and communal unity and solidarity.

Gangneung Danoje Festival A masked couple dancing at the Gwanno Mask Dance during the Dano festival, which is held to celebrate the change of the seasons from spring to summer.

The first event of the Danoje Festival is related to the preparation of “divine drinks” (sinju) to be offered to gods and goddesses, thus linking the human world with the divine world. This is followed by a variety of festive events such as the Gwanno Mask Dance, a non-verbal performance by masked players, swing riding, ssireum (Korean wrestling), street performances by farmers’ bands, changpo (iris) hair washing, and surichwi rice cake eating. Of these, the changpo hair washing event is particularly widely practiced by women who believe that the extract of changpo will give them glossier hair and repel the evil spirits that are thought to bear diseases.

Ganggangsullae

This traditional event combining a circle dance with singing and folk games was performed by women around the coastal areas of Jeollanam-do during traditional holidays such as Chuseok (Harvest Moon Festival/Thanksgiving) and the Daeboreum (the first full moon of the New Year on the lunar calendar) in particular.

While today only the dance part is selected to be performed by professional dancers, the original performance included several different folk games such as Namsaengi nori (Namsadang vagabond clowns’ play), deokseok malgi (straw mat rolling) and gosari kkeokgi (bracken shoot picking). The performers sing the Song of Ganggangsullae as they dance, and the singing is done alternately by the lead singer and the rest with the tempo of the song and dance movements becoming faster and faster towards the end.

Namsadang Nori

Namsadang nori, generally performed by an itinerant troupe of male performers, consisted of several distinct parts including pungmul nori (music and dance), jultagi (tightrope walking), daejeop dolligi (plate spinning),gamyeongeuk (mask theater) and kkokdugaksi noreum (puppet theater). The performers also played instruments while they danced, such as the barrel buk (drum), janggu (hourglass-shaped drum), kkwaenggari (small metal gong), jing (large metal gong), and two wind instruments called nabal and taepyeongso.

Yeongsanjae

Yeongsanjae, literally meaning “Rites of Vulture Peak”, is a Buddhist ritual performed on the 49th day after a person’s death to comfort his or her spirit, and guide it to the Buddhist land of bliss. The ritual, known to have been performed since the Goryeo Period (918-1392), consists of solemn Buddhist music and dance, a sermon on the Buddha’s teachings, and a prayer recitation. While it is an essential part of the Korean Buddhist tradition conducted to guide both the living and the dead to the realm of Buddhist truths and to help them liberate themselves from all defilement and suffering, it was sometimes performed for the peace and prosperity of both the state and the people.

1. Falconry It was once a serious activity conducted to gain food but now an outdoor sport seeking a unity with nature. 2. Namsadang Nori Performance presented by a traveling troupe of about 40 performers led by a percussionist called Kkokdusoe.3. Yeongsanjae A Buddhist memorial ritual performed on the 49th day after one’s death to guide the spirit to the pure land of bliss. 4. Pansori Performance of a solo artist assisted by a drummer where singing is combined with dramatic narratives and gestures to present a long, epic story (National Center for Korean Traditional Performing Arts).

Jeju Chilmeoridang Yeongdeunggut

This age-old shamanic ritual was at one time performed in almost all the towns and villages in Jejudo, with worshippers praying for a good catch and the safety of fishermen working at sea. According to the traditional folk belief of Jejudo islanders the second lunar month is the month of Yeongdeung, during which Grandma Yeongdeung, a wind deity, visits all the villages, farming fields and homes across Jeju, bearing tidings about the harvest in the oncoming autumn.

Taekkyeon

One of the surviving traditional martial arts developed in Korea, Taekkyeon, which is quite different from Taekwondo, used to be known by several different names such as Gakhui (“sport of legs”) and Bigaksul (“art of flying legs”), although such names suggest that it is related with the movement of kicking. Like most other martial arts in which weapons are not used, Taekkyeon is aimed at improving one’s self-defence techniques and promoting physical and mental health through the practice of orchestrated dance-like bodily movements, using the feet and legs in particular. Contestants are encouraged to focus more on defence than on offense, and to throw the opponent to the ground using their hands and feet or jump up and kick him in the face to win a match.

Jultagi

In the traditional Korean art of jultagi (tightrope walking), a tightrope walker performs a variety of acrobatic movements, as well as singing and comic storytelling, as he walks along a tightrope. He is generally assisted by an eorit gwangdae (clown) on the ground who responds to his words and movements with witty remarks and comic actions intended to elicit an amused response from the spectators. Tightrope walking was formally performed at the Royal Court to celebrate special occasions such as the (Lunar) New Year’s Day or to entertain special guests such as foreign envoys. However the aspiration of Joseon’s rulers towards a more austere lifestyle gradually pushed it toward villages and markets, and it ultimately became an entertainment for the common people. Whilst tightrope walking in other countries tends to focus on the walking techniques alone, Korean tightrope walkers are interested in songs and comedy as well as acrobatic stunts, thereby involving the spectators more intimately in the performance.

1. Taekkyeon A traditional Korean martial art marked by elegant yet powerful physical movements. 2. Jultagi Performance of tightrope walking combined with singing, comedy and acrobatic movements.

Falconry

Korea has a long tradition of keeping and training falcons and other raptors to seize quarry, such as wild pheasants or hares. Archaeological and historical evidence show that falconry on the Korean peninsula started several thousand years ago and was widely practiced during the Goryeo Period (918-1392) in particular. The sport was more popular in the north than in the south, and was conducted usually during the winter season when farmers were free from farm work. Falconers would tie a leather string around the ankle of their bird and an ID tag and a bell to its tail. The Korean tradition was inscribed on the Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity in 2010 along with those preserved in eleven other countries around the world including the Czech Republic, France, Mongolia, Spain, and Syria.

Arirang The most widely loved of all Korean folk songs, Arirang features the refrain “Arirang, Arirang, Arariyo.”

Arirang

Arirang is the name of a folk song sung by Korean people since olden times. There are many variations of the song, although the lyrics of their refrains have the words “arirang” or “arari” in common. The song was sung for many different purposes such as to reduce feelings of boredom during work, confess one’s true feelings to one’s beloved, pray to the divine being for a happy and peaceful life, and to entertain people gathered together for a celebration.

One element that has helped Arirang remain in the hearts of Korean people for so many years is its form, which is designed to allow any singer to easily add their own words to express their feelings. The importance of Arirang in the daily life of the Korean people is succinctly described in an essay, Korean Vocal Music, written in 1896 by Homer B. Hulbert (1863-1949), an American missionary and ardent supporter of Korean independence:

“The first and most conspicuous of this class is that popular ditty of seven hundred and eighty-two verses, more or less, which goes under the euphonious title of A-ri-rang. To the average Korean this one song holds the same place in music that rice does in his food?all else is mere appendage. You hear it everywhere and at all times.

The verses which are sung in connection with this chorus range through the whole field of legend, folklore, lullabies, drinking songs, domestic life, travel and love. To the Korean they are lyric, didactic and epic all rolled into one. They are at once Mother Goose and Byron, Uncle Remus and Wordsworth.”

Kimjang: Making and Sharing Kimchi in Korea

Kimjang is the activity of making kimchi that is conducted all over Korea during late autumn as part of the preparations to secure fresh, healthy food for the winter season. Now gaining a worldwide reputation as a representative Korean food, kimchi has always been one of the key side dishes required to complete the everyday meals eaten by Korean people since olden times. That is why Kimjang has long been an annual event of paramount importance for entire families and communities across Korea.

The preparations for making kimchi for the winter season follow a yearly cycle. In spring, households procure a selection of seafood including shrimps and anchovies in particular, which they salt and leave to ferment until they are ready for use in the Kimjang season. They then obtain fine-quality sun-dried sea salt in summer and prepare red chili powder and the main ingredients, kimchi cabbage and Korean white radish, in autumn. Then, with winter approaching, members of families and communities alike gather together on a mutually agreed date to make kimchi in sufficient quantities to sustain families with fresh food through the long, harsh winter.

While Korea is now a modern, industrialized nation, the ageold tradition of making kimchi is still maintained as a collective cultural activity contributing to a shared sense of social identity and solidarity among today’s Korean people. The tradition was registered by UNESCO on its Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity on December 5, 2013.

World Heritage Sites

1 Seokguram Grotto and Bulguksa Temple

Archetypes of Buddhist architecture developed in Silla.

Location Gyeongju-si, Gyeongsangbuk-do

Website www.sukgulam.org

2 Janggyeongpanjeon Depositories of Haeinsa Temple, Hapcheon

The oldest buildings at Haeinsa Temple, storing over 80,000 woodblocks of the Tripitaka Koreana.

Location Hapcheon-gun, Gyeongsangnam-do

Website www.haeinsa.or.kr

3 Jongmyo Shrine

A Confucian shrine storing the memorial tablets of Joseon’s Kings and their Queen Consorts.

Location Jongno-gu, Seoul

Website jm.cha.go.kr

4 Changdeokgung Palace

The official Royal Palace of the Joseon Dynasty for 258 years from 1610 to 1868.

Location Jongno-gu, Seoul

Website www.cdg.go.kr

5 Hwaseong Fortress

An architectural masterpiece of Joseon fortifications combining beauty and practicality.

Location Suwon-si, Gyeonggi-do

Website www.swcf.or.kr

6 Gyeongju Historic Areas

The well preserved remains of Gyeongju, the capital of Silla for one millennium.

Location Gyeongju-si, Gyeongsangbuk-do

Website guide.gyeongju.go.kr

7 Gochang, Hwasun and Ganghwa Dolmen Sites

Countless lithic monuments dating from prehistoric Korea.

Location Gochang-gun of Jeollabuk-do,Hwasun-gun of Jeollanam-do, and Ganghwa-gun of Incheon

8 Jeju Volcanic Island and Lava Tubes

Volcanic cones and lava tubes formed by eruptions of Mount Hallasan, the highest mountain in South Korea

Location Hallasan Mountain, Geomunoreum, and Ilchulbong of Seongsan, Jejudo Island

Website jejuwnh.jeju.go.kr

9 Royal Tombs of the Joseon Dynasty

Fifty-three Royal Tombs of the Joseon Dynasty preserved in their original condition.

Location Seocho-gu of Seoul, and Guri-si and Yeoju-si in Gyeongggi-do

10 Historic Villages of Korea: Hahoe and Yangdong

Villages formed by aristocratic families of Joseon based on Confucian ideology.

Location Andong-si and Gyeongju-si, Gyeongsangbuk-do

11 Namhansanseong

A Mountain fortress that served as a temporary capital during the Joseon Dynasty, showing how the techniques for building a fortress developed during the 7th -19th centuries.

Location Gwangju-si, Gyeonggi-do

Memory of the World

12 Hunminjeongeum (The Proper Sounds for the Instruction of the People)

A single-volume xylographic book printed in 1446, containing commentaries on the Korean writing system.

13 Joseon Wangjo Sillok: Annals of the Joseon Dynasty

A huge collection of the annals of the Joseon dynasty from 1392 to 1863, bound in 1,893 volumes in 888 books.

Website sillok.history.go.kr

14 Baegun Hwasang Chorok Buljo Jikji Simche Yojeol (vol. II), the second volume of an “Anthology of Great Buddhist Priests' Zen Teachings”

An advanced-level textbook published for monk-scholars in medieval Korea.

Website www.jikjiworld.ne

15 Seungjeongwon Ilgi: Diaries of the Royal Secretariat

Daily records of Joseon’s rulers, containing a wealth of historical information.

Website kyu.snu.ac.kr

16 Uigwe: Royal Protocols of the Joseon Dynasty

Rare and exquisite collections of illustrated records on important state and royal occasions of the Joseon Dynasty.

Website kyujanggak.snu.ac.kr

17 Printing Woodblocks of the Tripitaka Koreana and Miscellaneous Buddhist Scriptures

A superb collection of the Buddhist canon of scriptures carved on 80,000 woodblocks, providing valuable information on the politics, culture and philosophy of Goryeo in the 13th century.

Website www.haeinsa.or.kr

18 Dongui Bogam: Principles and Practice of Eastern Medicine

An encyclopedic work on medicine developed in East Asia since ancient times.

19 Ilseongnok: Daily Records of the Royal Court and Important Officials

Diaries kept by Joseon rulers between 1752 and 1910, containing records of state affairs and the daily activities of Joseon’s Kings.

20 Human Rights Documentary Heritage 1980 Archives for the May 18th Democratic Uprising against Military Regime, in Gwangju

A vast collection of documents, videos, photographs, etc. on the democratic movements that spread in and around Gwangju in May 1980.

21 Nanjung Ilgi: War Diary of Admiral Yi Sun-sin

A collection of private journals kept by Admiral Yi Sun-sin, recording his daily activities and battle situations during the Imjin Waeran (Japanese Invasion, 1592- 1598).

22 The Archives of Saemaeul Undong

A collection of historical records on the Saemaeul Undong (“New Community Movement”), an exemplary movement that led to the successful development of farming communities and the eradication of poverty in the 1970s.

Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity

23 The Royal Ancestral Rituals and Music at the Jongmyo Shrine

A traditional performance of music, song and dance presented during the memorial rite held at the Royal Ancestral Shrine.

24 Pansori

The traditional art of the dramatic song performed by a solo performer to the accompaniment of a single drummer, presenting an epic story by combining singing, narratives and gestures.

25 Gangneung Danoje Festival

A time-honored summer festival held on the 5th day of the 5th lunar month.

26 Ganggangsullae

A traditional folk entertainment with singing and dancing performed by women to celebrate moon festivals.

27 Namsadang Nori

Folk performances traditionally presented to rural communities by an itinerant troupe of about forty performers (Namsadang) led by the chief musician (Kkokdusoe).

28 Yeongsanjae

A Buddhist ritual performed to comfort and guide the spirits of the dead to the Buddhist land of bliss.

29 Jeju Chilmeoridang Yeongdeunggut

A traditional shamanic ritual practiced at Chilmeoridang, a shrine for the village tutelary of Geonip-dong, Jeju-si.

30 Cheoyongmu

A Court dance performed by five dancers wearing Cheoyong masks and costumes in five cardinal colors.

31 Gagok, Lyric Song Cycles Accompanied by an Orchestra

Traditional vocal music performed by putting a poem to a melody with an accompaniment of orchestral music.

32 Daemokjang, Traditional Wooden Architecture

The art of building traditional works of architecture designed and supervised by a master builder.

33 Falconry

The traditional art of keeping falcons and training them to hunt for quarry.

34 Jultagi

A traditional folk entertainment in which a tightrope walker performs acrobatic movements and tells comic stories as he walks along the rope.

35 Taekkyeon

A traditional Korean martial art practiced for self-defence purposes and known to be beneficial to one’s physical and mental health.

36 Weaving of Mosi (fine ramie) in the Hansan Region

The tradition of weaving ramie, a fine-quality fabric used for the production of summer clothing, preserved in Hansan.

37 Arirang

A folk song with many variations cherished by the Korean people throughout history.

38 Kimjang, Making and Sharing Kimchi in Korea

The cultural tradition of preparing for and making kimchi to be eaten during the winter season, typically with the participation of an entire family or community.

The source of this article is from Cultural Heritage Administration site.

The link= <http://www.korea.net/AboutKorea/Culture-and-the-Arts/UNESCO-Treasures-in-Korea

댓글 없음:

댓글 쓰기